By: Vasundhara

Source: Just be there, it’s enough! | /r/wholesomememes | Wholesome Memes | Know Your Meme

In the intricate web of human relationships, the way we communicate and connect with others shapes our social landscape. But what if I told you that sharing negative experiences could hold the key to forging deeper bonds and synchronizing our brains with those around us? Have you instantly felt closer to someone after sharing your bad experience with someone? As it turns out, there may be more to this instinct than meets the eye. While prior work has examined the benefits of sharing positive emotions, the effects of disclosing negative experiences have been more mixed and less well-understood.

To share my personal experience, I have always been hesitant to open about my insecurities and fears with anyone. However, I remember very early in my school there was this session on mental health, where I had the chance to share about my anxiety and self-doubt. To my surprise, my classmates responded with empathy, sharing their own experiences and offering words of encouragement and thus fostering a culture of openness and support

Empathy: a possible bridge for pro- social behaviour?

When we share our negative experiences, it’s like diving deep into a pool together. We’re immersed in each other’s worlds, fostering a deeper understanding and empathy. Expressing your thoughts and emotions can make you more understanding, especially during conflicts (Sels et al., 2021). Also, when we see someone else going through a tough time or needing help, it can make us more empathetic (Crick and Dodge, 1994). Isn’t that true that when we feel more empathy, we tend to pay more attention to what others need and how they feel? This can lead us to behave in ways that help them, which is called prosocial behaviour (Batson et al., 1995).

Interpersonal liking facilitating pro-social behaviour

Imagine having a heart-to-heart conversation where you and your companion feel completely in sync, like you’re dancing to the same beat. And that’s exactly what happens in self-disclosure. Self – disclosure argument often invokes feelings of trust and intimacy as while one is having a conversation and both the parties feel that they are “in sync” and leaves to the temporary feeling of being on the same wavelength. Apparently, these shared experiences favours interpersonal liking and social closeness (Xie et al., 2021), as well as subsequent mutual prosociality (Hu et al., 2017). Could it be that sharing our negative experiences fuels this cycle of empathy and support?

What goes on in the brain while you are having conversations with others?

To possibly know as to what is going on inside the brain during conversations researchers use the hyper scanning technique for measuring the brain activity of two or more individuals simultaneously (Montague et al., 2002). And it has been seen in studies that during social interactions there is Interpersonal Neural Synchronization (INS) which refers to the phenomenon where the brain activity of two or more individuals becomes synchronized during social interactions.

Previously, it’s unclear if INS plays a role in disclosing negative experiences and its link to social dynamics like empathy and liking. Led by Xiaojun Cheng and colleagues from Chinese universities (2024), aimed to investigate this aspect of self-disclosure, so let us deep dive into it

What was the study?

Picture this: 96 college students, all strangers to each other, brought together in 48 same-gender pairs. These pairs were randomly assigned to either share their own personal struggles (the self-disclosure group) or recount the hardships of unknown others (the non-disclosure group). Armed with their own narratives of recent experiences, both neutral and negative, these participants embarked on an experiment that would delve into the depths of human connection.

The Experiment:

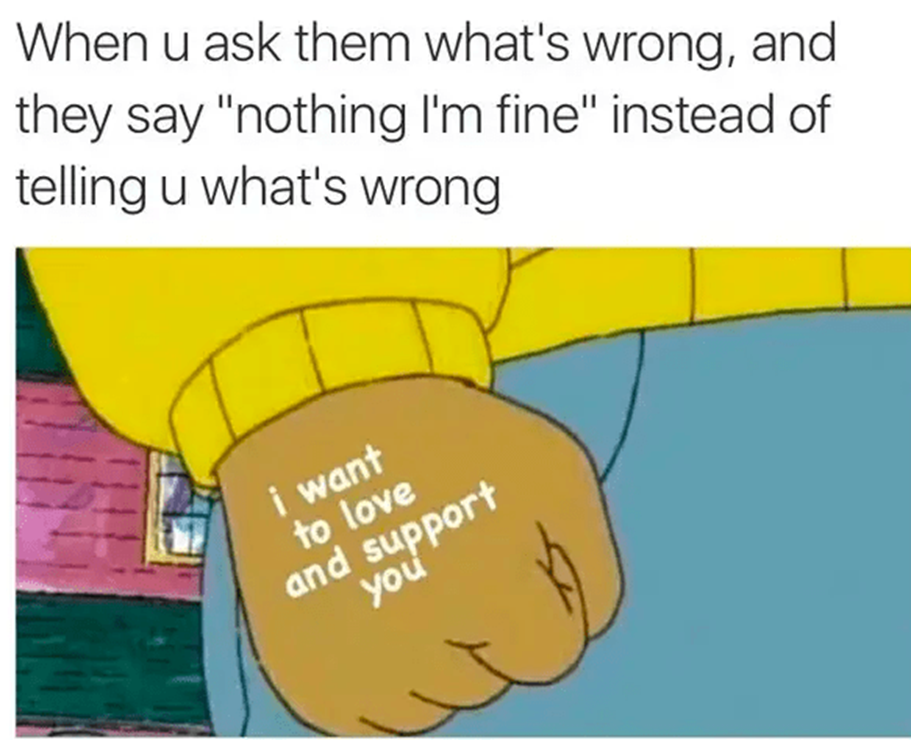

Before starting the experiment, participants wrote narratives about their experiences, ranging from everyday events to distressing moments. They then took turns sharing these experiences, alternating between neutral and negative topics. One participant would share while the other listened attentively, followed by open communication about the shared experience. Crucially, researchers used functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) hyper scanning to monitor the brain activity of these pairs. This technique measured how synchronized the brain activities of the discloser and listener became during their interactions (INS) (Figure 1).

Fig.1. Experimental design and setup

What did we find out?

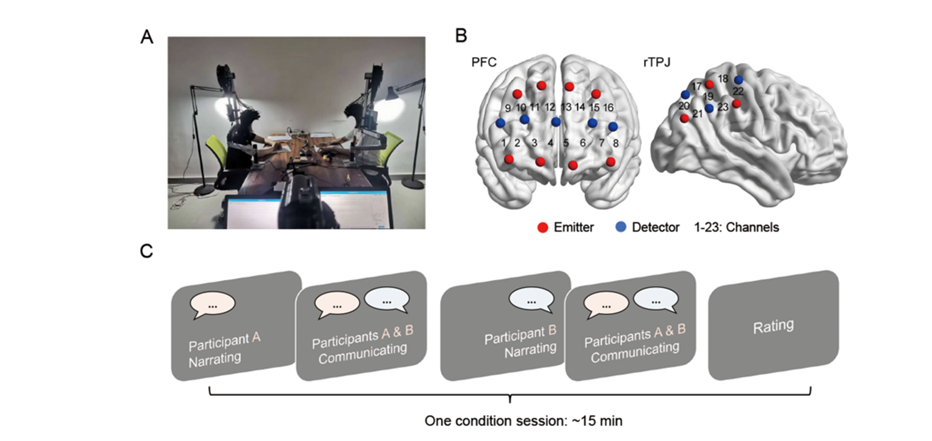

The results were quite remarkable. Compared to sharing neutral experiences, sharing negative experiences led to several positive social outcomes – including increased prosocial behaviour, emotional empathy, and interpersonal liking. But the truly fascinating finding according to me was that these effects were amplified in the self-disclosure group compared to the non-disclosure group (Figure 2). One reason for this amplification could be the presence of positive affect, enhancing engagement and promoting prosocial behaviours. (For eg: “I hear your bad experience àI feel bad à I feel like helping you”). Also, another important caveat here is how responsive you are being to the other person and if you are a responsive partner then that promotes feelings of closeness and intimacy. (Regan et al., 2022)

Neural Mechanisms during the disclosure

Let’s delve into the inner workings of the brain to uncover why sharing negative experiences can deepen connections. Picture this: you’re confiding in a friend about a recent setback, like a tough breakup or a job loss. Research by Schilling et al. (2013) shows that when you open up about these challenges, something fascinating happens in your brain.

Instead of just chatting about mundane topics, discussing difficult experiences activates a specific brain region called the left superior frontal cortex (l-SFC). Now, this isn’t just any brain area – it’s like the maestro of your mind, orchestrating emotions, attention, and even your sense of self. So, when it lights up during heartfelt conversations, it’s like your brain’s way of saying, “We’re really tuning in to each other now!”

Think of it like this: when you’re sharing a tough experience, your brain goes into overdrive, ensuring that you and your friend are truly connecting. This synchronization in the l-SFC is akin to tuning in to the same radio station together, where you’re both experiencing the same emotions and fully grasping each other’s perspectives.

And here’s the kicker – this brain synchronicity isn’t just a neat trick. It’s associated with some powerful outcomes, such as heightened emotional empathy and a stronger affinity for each other. (Figure 2) Essentially, your brains are syncing up, fostering a deeper sense of connection as well as understanding your own emotions better.

Thus, to summarise Cheng et al. study emphasise that revealing one’s own struggles seems to elicit a deeper empathetic response, leading to heightened altruism and support.

When we share our vulnerability, it invites others to do the same. It’s through this mutual exchange of openness and honesty that we deepen our connections and foster genuine empathy and understanding.

– Dr. Daniel Goleman (American Psychologist and author)

Implications and Future Directions

The study suggests that encouraging people to share their own negative experiences, rather than just listening to the problems of others, may be a more effective way to promote prosocial behaviour and social harmony. Hence, that highlights the importance of creating safe and supportive environments where people feel comfortable being vulnerable and authentic. In order to do that there can be few steps that can be taken: –

- Fostering Open Communication: Let’s create spaces where honest and transparent conversations thrive. By sharing our thoughts and experiences openly, we pave the way for deeper connections and understanding.

- Embracing Imperfection: Vulnerability is not a weakness; it’s a testament to our shared humanity. Let’s embrace imperfection and allow ourselves to be authentic, even when faced with uncertainty or discomfort.

- Seeking Support: Don’t go it alone. Whether it’s confiding in a trusted friend, seeking therapy, or joining a support group, acknowledging our vulnerabilities is the first step toward healing and growth.

Sharing negative experiences can wield surprising social benefits, yet further research is needed to grasp the full spectrum of its effects. While some studies reveal adverse outcomes, particularly in cases of collective trauma or PTSD, the social context appears to be the determining factor. With the researchers focusing on a limited sample, it remains uncertain if these effects endure over time or across diverse populations.

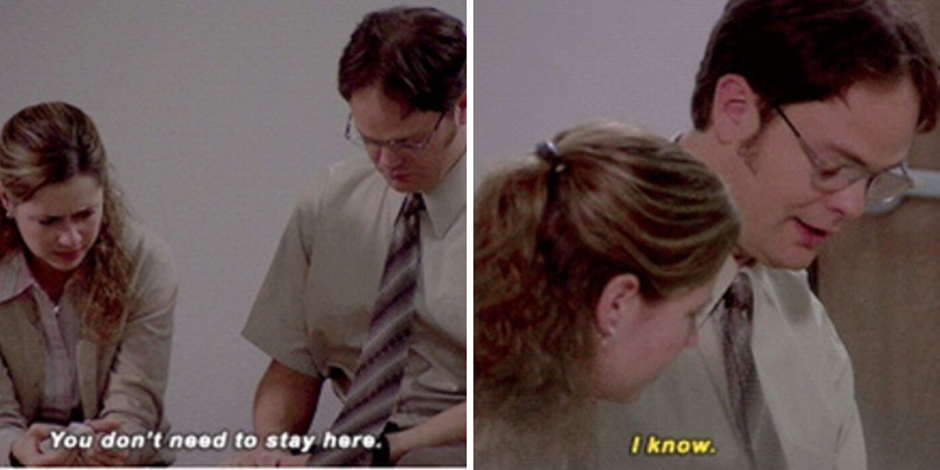

Source: The Office: 10 Times Dwight & Pam Were Actually Best Friends (screenrant.com)

Nevertheless, this study challenges the idea that negative experiences should be concealed, advocating instead for openness to foster connection and inspire prosocial behaviour. In essence, when a friend confides in you, embracing openness and active listening can forge deeper bonds and motivate supportive actions. Let’s not forget the importance of encouraging vulnerability, especially in workplaces where it’s often stigmatized as being unprofessional. After all, vulnerability is the cornerstone of genuine connection and growth.

References

Cited Article: Cheng, X., Wang, S., Guo, B., Wang, Q., Hu, Y., & Pan, Y. (2024). How self-disclosure of negative experiences shapes prosociality?. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 19(1), nsae003

Crick, N.R., Dodge, K.A. (1994). A review and reformulation of social information-processing mechanisms in children’s social adjustment. Psychological Bulletin, 115(1), 74–101

Hu, Y., Hu, Y.Y., Li, X.C., Pan, Y.F., Cheng, X.J. (2017). Brain-to-brain synchronization across two persons predicts mutual prosociality. Social Cognitive & Affective Neuroscience, 12(12), 1835–44.

Motsenok, M., Kogut, T., & Ritov, I. (2022). Perceived physical vulnerability promotes prosocial behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(2), 254-267.

Regan, A., Rado, N., Lyubomirsky, S. (2022). Experimental effects of social behavior on well-being. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26(11), 987–98.